Player pianos have come a long way since they were invented in the late 1800s, but I came across an old-school system that merges the old with the new in a really cool way.

It turns out the owner is a retired (old school) player piano technician who had his Mason & Hamlin upright with a Welte-Mignon player system modified with the help of an electronics expert to play midi files digitized from player rolls.

While the original player system does function in the traditional way with a paper roll, being able to play the midi files from a computer has certain advantages, such as avoiding wear and tear on the delicate paper rolls and continuous play rather having to regularly switch out player rolls in order to listen to something else.

But, digitizing player piano rolls goes far beyond making life easier for my client. Because although he is technically retired, he still spends a lot of time tracking down and scanning player piano rolls in collaboration with Stanford University as part of The Player Piano Project.

The Player Piano Project is dedicated to the preservation of player pianos and player piano rolls, especially with regard to their role as primary sources of performance history. While player rolls are for the most part considered obsolete these days, the rolls played an important role (ha!) in recording and reproducing music of the late 19th and early 20th century, before the advent of of the phonograph.

Along with researchers and teachers, enthusiasts such as my client and his fellow members of the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors Association (AMICA) are participating in The Player Piano Project by helping locate, scan and digitize player piano rolls worldwide.

The eventual goal is to have a database of every player roll ever to have been produced along with the digitized file for archival as well as public enjoyment purposes.

As a music nerd, a classical music nerd to be specific, the coolest thing about player rolls is that some contain performances of composers, including Debussy, Prokofiev and Gershwin playing their own works, as well as performances by renowned concert pianists. There is also a lot of music from that time that was popular then but has since been forgotten. Such recordings from that time are scarce or nonexistent, and it is awesome to me that player rolls provide a way to go back in time and hear anything at all from that era.

It all starts with learning of a player roll’s existence.

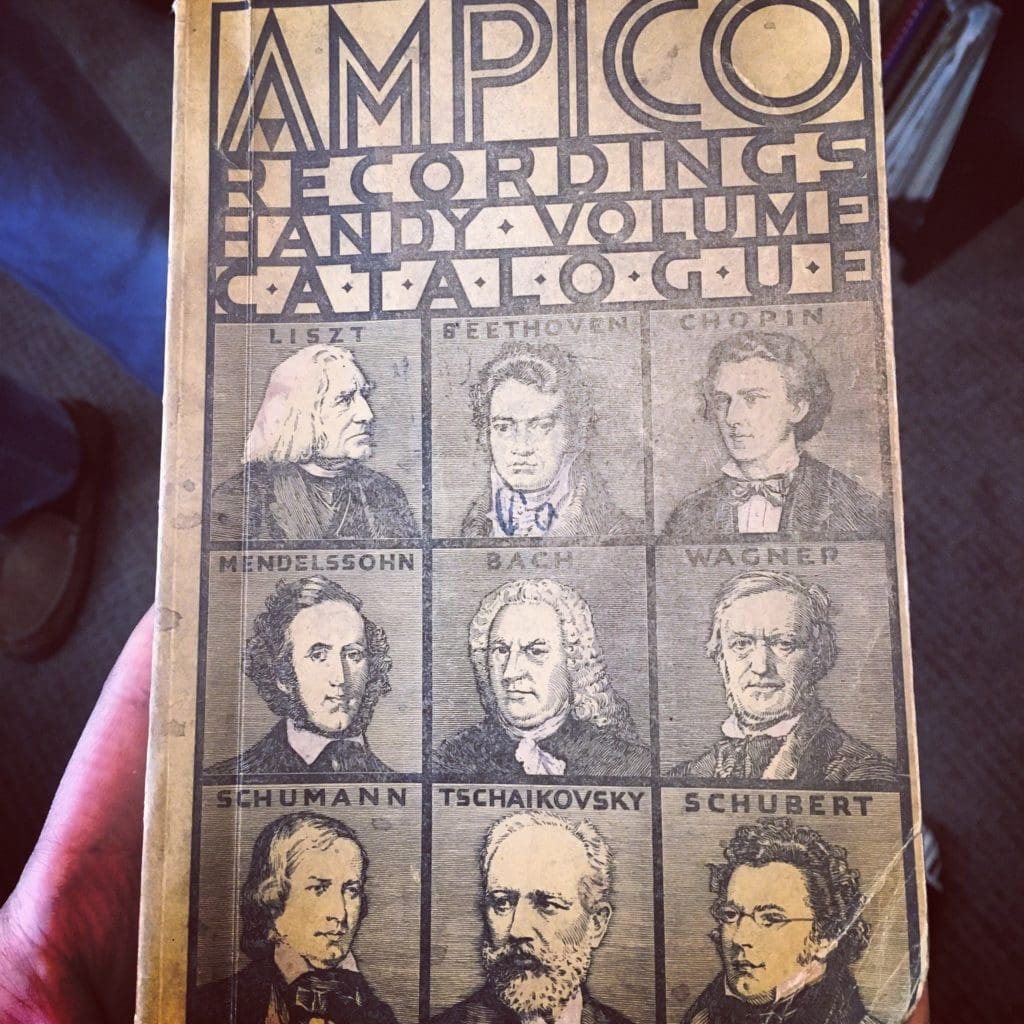

This information can come from a variety of sources — a box unearthed when cleaning out a grandparent’s attic is posted on Craigslist, a player roll manufacturer’s catalogue, perhaps the meticulous records of a librarian in Spain.

Whatever the source, my client, alongside his fellow AMICA members and other enthusiasts, is always on the lookout of previously unknown rolls to add to the database. He researches and tracks down player rolls in far-flung corners of the world, all in a race against time to preserve the music contained within the fragile paper before it ends up being forgotten (again), damaged, or even worse, thrown away.

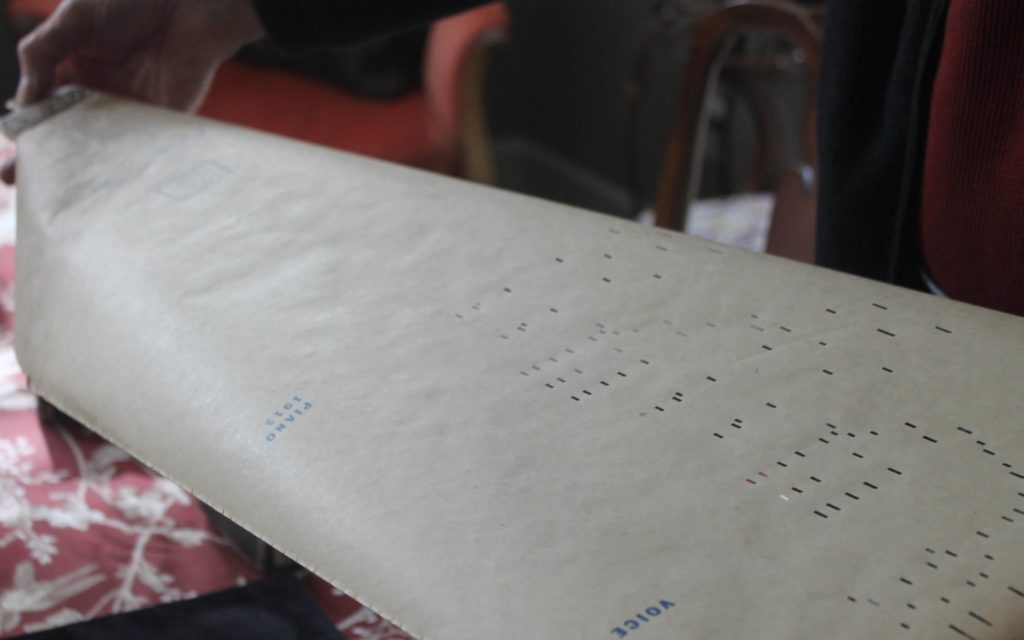

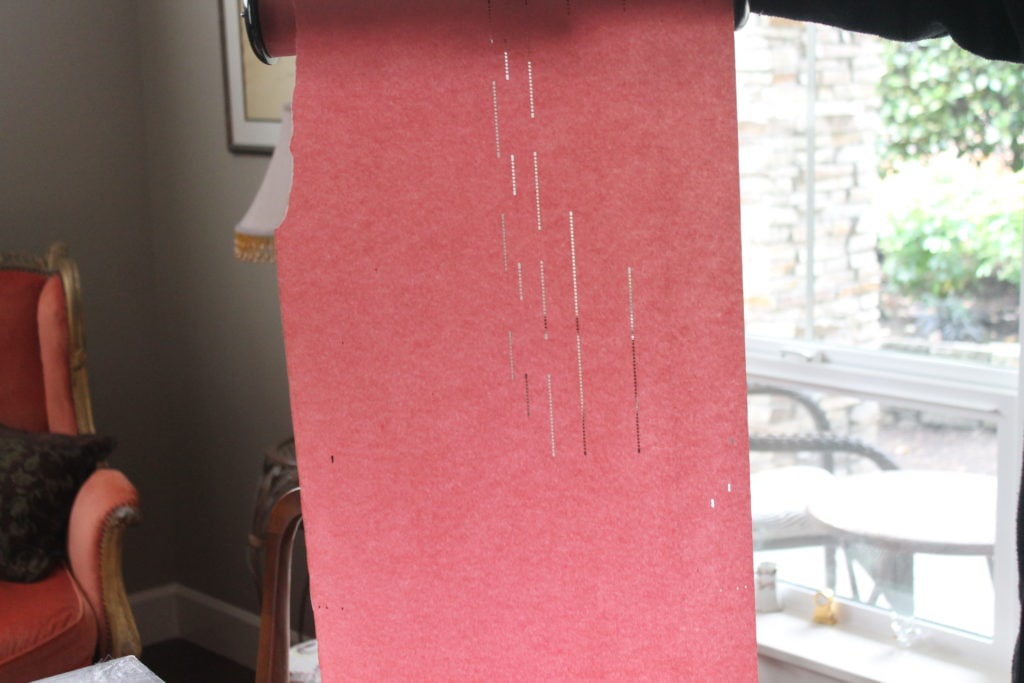

The first step in the digitizing process is to run the player roll through a specialized scanner. With 90 columns of information to capture (88 keys plus two pedals), a normal office scanner won’t get the job done.

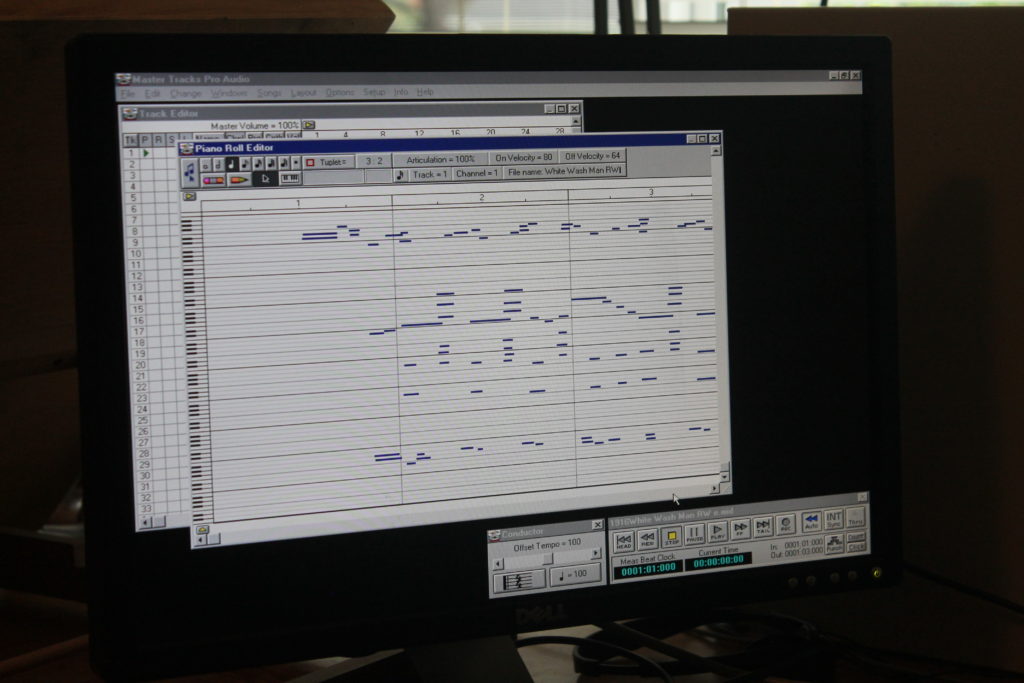

The specialized scanner records the perforations in the paper roll, creating a scanned file which is then run through a player roll editing program, which in turn converts the information into a MIDI format file.

Sometimes, manual editing is necessary, either to correct alignment issues from the multiple files needed for one roll, or to correct imprecise information due to player roll damage. Some player roll experts are so adept that they can “read” the music based on the note punchings in the player roll or in the MIDI file!

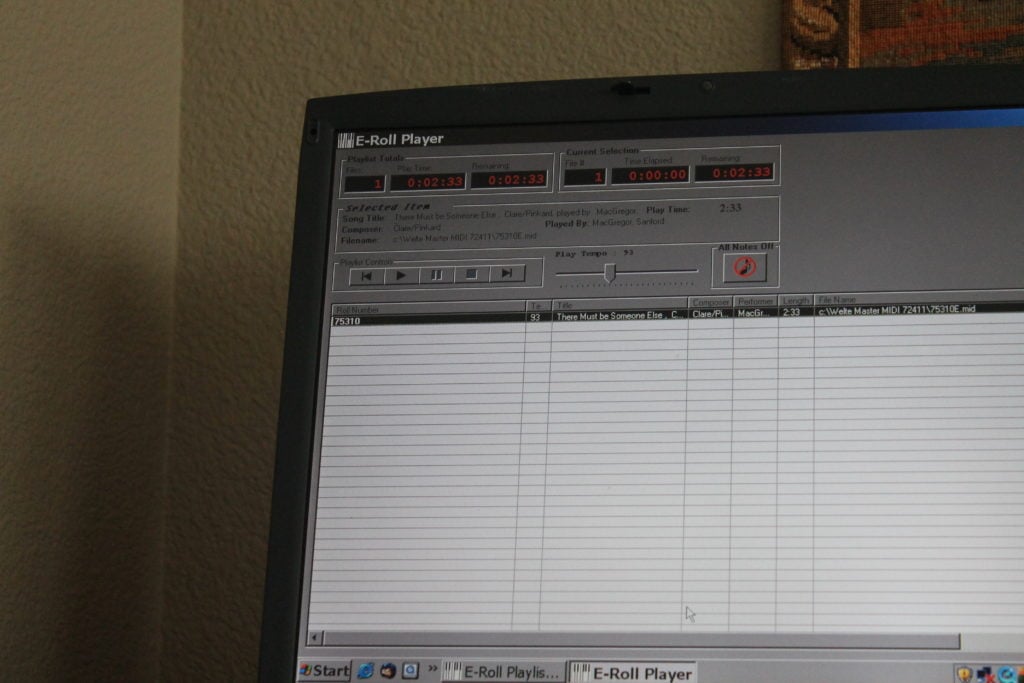

From there, the scanned files can be loaded into a computer program from which the files can be played on an appropriately modified player system, such as my client’s, or loaded onto a USB and played using a modern player platform, such as a Yamaha Disklavier, PianoDisc, or QRS system.

I once asked my piano professor in college if he ever felt like he had had a perfect performance, and he replied that he hadn’t but that he did have performances he was happy with. His comment reminded me that there is no such thing as perfection in music because all music is but moment in time, something fleeting that changes from day to day, just like the people who interpret it, even when that player may be the composer.

It makes what The Player Piano Project, my client, and AMICA are doing all the more valuable because they are preserving these rare, fleeting moments from an era when recording was not just a matter of pulling out an iphone, but a huge, expensive, rare undertaking.